Introduction

[In Public Choice Theory And The Illusion Of Grand Strategy], Richard Hanania details how a public choice model (imported from public choice theory in economics) can explain the United State’s incoherent foreign policy much better than the unitary actor model (imported from rational choice theory in economics) that underlies the illusion of American grand strategy in international relations (IR), in particular the dominant school of realism. As the subtitle How Generals, Weapons Manufacturers, and Foreign Governments Shape American Foreign Policy suggests, American foreign policy is driven by special interest groups, which results in millions of deaths for no good reason.

In the unitary actor model, the primary unit of analysis of inter-state relations is the state as a monolithic agent capable of making rational decisions (forming coherent, long-term “grand strategy”) from cost-benefit analysis based on preference ranking and expected “national interest” maximisation.

In the public choice model, small special-interest groups that reap a large proportion of the benefits from a policy (concentrated interests) are much more incentivised to lobby for a policy than the general public who pay for a negligible portion of the cost of the policy (diffused interests) are incentivised to lobby against. The former can coordinate much easier than the latter that has to overcome rational ignorance (the cost of educating oneself about foreign policy outweighs any benefit an one can expect to gain as individual citizens cannot affect foreign policy) and the society-wide collective action problem (irrational for every citizen to cooperate in the prisoner’s dilemma especially if individual gain is negligible) resulting in inefficient (not-public-good-maximising) policymaking i.e. government failure.

It is very much an academic book that should revolutionise the whole field of IR by challenging the fundamental assumption of realpolitik with impressive rigour, so the brisk 200 pages should probably be mandatory reading for IR/political science freshmen. Like Robin Hanson, I would have been persuaded by an article length analysis, but as Hanania himself agrees, the belabouring book length treatment is to disabuse academics who by nature demand sweat and impressive mastery of literatures — this review should, dare I say, suffice for the cynical reader.

1. Goodbye Unitary Actor Model

IR theorists have put forth three justifications for the unitary actor model.

First, Morgenthau argued that human nature is intrinsically aggressive, so states seek to dominate one another in the struggle for power. But this begs the question of why the collective action problem inherent to large-scale cooperation within hierarchic political organisation is overcome at the level of states.

Second, Mearsheimer, Bosen, and Waltz argued that nationalism is strong enough to make states act like unitary actors. However, nationalism only appears strong when compared to the pull of universalist ideologies like Marxism or liberalism, because soldiers can continue fighting for their fellow combatants despite widespread disillusionment with the mission itself as seen in the Iraq war. Nationalism is weaker than financial self-interest, as no viable army can exist without paying soldiers market salary, and states need laws like tariffs to protect domestic industry; nationalism is also weaker than familial interests, as states need laws against nepotism.

Third, Waltz argued that states behave as unitary actors because those that do not get overtaken by those that do. The Darwinian or market selection analogy breaks down as there are only very few states at any point in history i.e. insufficient units for selection, and conquest has disappeared from international society i.e. selection pressure does not exist.

Other IR theorists have argued that the unitary executive model can save the unitary actor model but Hanania argues that they, too, fall short.

First, Milner and Tingley argued that US presidents are more constrained in policy areas with concentrated interests (e.g. trade, foreign aid, immigration), and less constrained in policy areas with diffused interests i.e. public goods (e.g. geopolitical aid, deployment of force, sanctions), so American foreign policy has the tendency to militarise. Alas, voters have short memories — an election with the president’s party on the ballot is never more than two years away, so the president should constantly be seeking to help his own party, even when not facing the voters himself. A “grand strategy” based on a biennial election calendar is not much of a grand strategy at all.

Second, Posner and Vermeule argued that the executive branch of the US government can be considered a united force capable of outmanoeuvring a Congress divided by power, which leads to a federal government that is more responsive to public opinion via elections and politics (rather than laws) to better solve problems. Afterall, politicians are political — they are selected based on their ability to convince others of their sincerity, likability, and competence, not necessarily their ability to solve problems, and especially not to solve problems that will arise after they have left office.

2. Hello Public Choice Model

Public choice theory was developed to understand domestic politics, but Hanania argues that public choice is actually even more useful in understanding foreign policy.

First, national defence is “the quintessential public good” in that the taxpayers who pay for “national security” compose a diffuse interest group, while those who profit from it form concentrated interests. This calls into question the assumption that American national security is directly proportional to its military spending (America spends more on defence than most of the rest of the world combined).

Second, the public is ignorant of foreign affairs, so those who control the flow of information have excess influence. Even politicians and bureaucrats are ignorant, for example most(!) counterterrorism officials — the chief of the FBI’s national security branch and a seven-term congressman then serving as the vice chairman of a House intelligence subcommittee, did not know the difference between Sunnis and Shiites. The same favoured interests exert influence at all levels of society, including at the top, for example intelligence agencies are discounted if they contradict what leaders think they know through personal contacts and publicly available material, as was the case in the run-up to the Iraq War.

Third, unlike policy areas like education, it is legitimate for governments to declare certain foreign affairs information to be classified i.e. the public has no right to know. Top officials leaking classified information to the press is normal practice, so they can be extremely selective in manipulating public knowledge.

Fourth, it’s difficult to know who possesses genuine expertise, so foreign policy discourse is prone to capture by special interests. History runs only once — the cause and effect in foreign policy are hard to generalise into measurable forecasts; as demonstrated by Tetlock’s superforecasters, geopolitical experts are worse than informed laymen at predicting world events. Unlike those who have fought the tobacco companies that denied the harms of smoking, or oil companies that denied global warming, the opponents of interventionists may never be able to muster evidence clear enough to win against those in power with special interests backing.

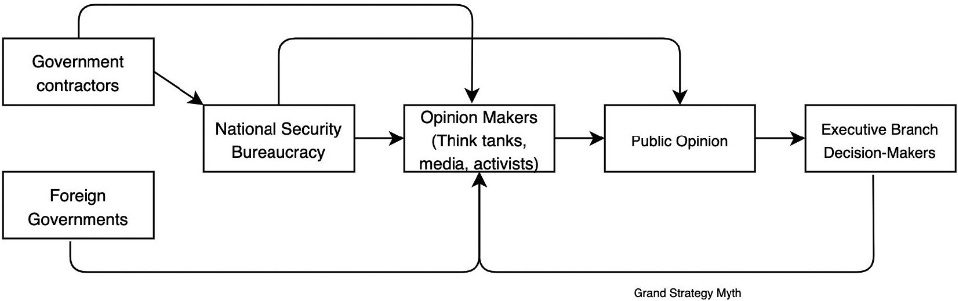

Hanania’s special interest groups are the usual suspects: government contractors (weapons manufacturers [1]), the national security establishment (the Pentagon [2]), and foreign governments [3] (not limited to electoral intervention).

What doesn’t have comparable influence is business interests as argued by IR theorists. Unlike weapons manufacturers, other business interests have to overcome the collective action problem, especially when some businesses benefit from protectionism. By interfering in a foreign state, the US may build a stable capitalist system propitious for multinationals, but can conversely cause a greater degree of instability and make it impossible to do business there; when business interests are unsure what the impact of a foreign policy will be for their bottom line, they should be more likely to focus their lobbying efforts elsewhere.

The mechanism of influence is outbidding all other competitors in the marketplace of ideas, by

donating to the most influential think tanks in Washington (the United Arab Emirates to CSIS; Qatar to Brookings Institution);

funding movements, as in the case of neoconservatives who pushed for Saddam’s overthrow, the movement was spearheaded by PNAC (created by Lockheed Martin) lobbyists who would go on to become Bush administration officials like Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Cheney and Weber;

bureaucratising public opinion management (the supposedly independent and neutral RAND Corporation gets 80% of its funding from the federal government);

boxing in the president’s major foreign policy decision via military generals’ press manipulation (MacArthur commenting on escalating engagement in the Korean War before he was fired by Truman; top generals in the Obama administration publicly discussing troop commitment needed to win in Afghanistan)

shaping foreign policy reporting from propagandistic journalists in the close-knit ‘foreign policy community’ (former Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland is literally the wife of neocon author Robert Kagan)

‘revolving doors’ for all three concentrated interest to actively collaborate (80% of retired three- and four-star generals between 2004 and 2008 went on to work as consultants or executives in the defence industry; ‘rent-a-general’ like the Four Star Group in which generals leverage their Pentagon contacts to consult in equity investing)

You know the book is dry when this is one of the only two graphics.